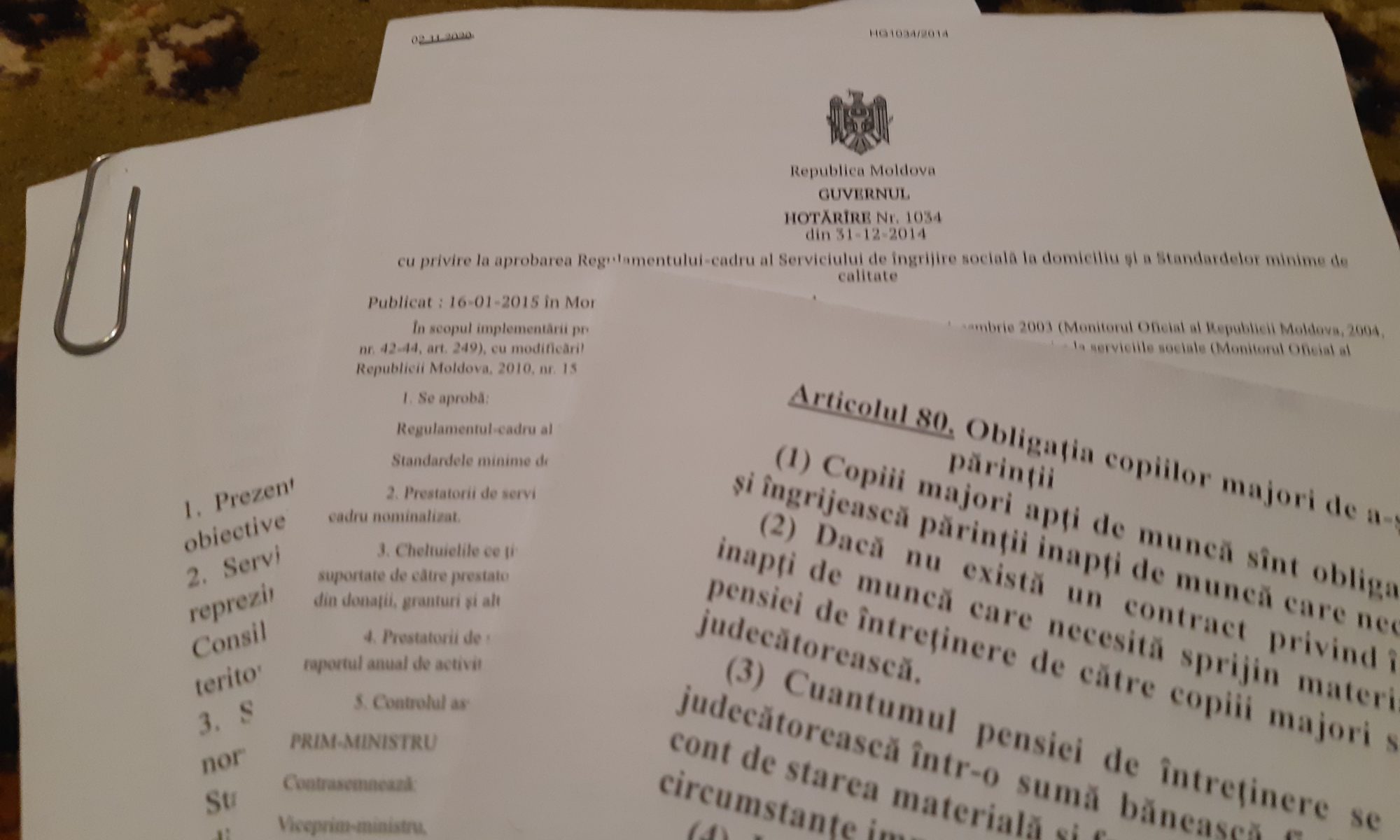

The last couple of weeks have been intense and full of fascinating input. This blog update will try to highlight some of them. The picture shows an interview with three home care workers in a village in Northern Moldova; for pandemic-related reasons the interview was performed outdoors.

While carrying out a number of interviews and observations, one thing has become a lot clearer: Elderly care workers in Moldova do spend considerable time supporting care-takers emotionally. As previously stated, talks (“convoribiri”) amount to the most commonly performed intervention during care work, but this is also regarded the most important of them all, both from care-takers and staff’s perspective. They may have considerable duration in time and occur every second day. This contrasts sharply with Swedish home care practice, characterized by short but frequent interventions.

As a Moldovan care-taker is admitted home care, a number of hours is assigned and a schedule established. Typically, the schedule (“grafic”) allows for a two-hour visit every second day, by one care-giver. Together, the care receiver (“beneficiar/a”) and the staff agrees on what needs to be done. While shopping for food, taking care of the house, helping out with preparing food, and making errands at the postal office or the pharmacy are frequently occuring task; talks & consultation takes place at almost every visit. In case a care receiver needs more time on a specific day, staff may call to the person next on the list to announce a later arrival. It’s however not feasible, or at least not sustainable, to reoccuringly spend more than the assigned number of hours, or to come at a more frequent pace – like every day or several times per day (although some staff admit to that they occasionally step out of their work schedule to make additional visits at care receivers who are in especially dire need).

This order of things differs radically from how Swedish home care is designed. There, the normality could be described as consisting of a number of very short visits per day. Care takers may be admitted help with getting out of bed, making breakfast, performing intimate care, etc – all of which may be divided into a number of short interventions. Since actions related to food, intimate hygiene, movement, and getting dressed and undressed occur in large numbers in Sweden, one may wonder why they are not mentioned in the Moldovan home care. Interviewees have given two explanations:

- Few people have this sort of needs. Most can get out of bed, put coffee on the table, or take care of their intime hygiene by themselves.

- Those that are in such an advanced state of ageing that they can not manage this any more, will anyway not have too many more months left to live, so that when those things occur, this type of interventions will not have to last for very long.

Alternatively, it may be possible that a lot of people feel uncomfortable to ask for this kind of help, because they know it’s unusual, or they’re too proud to admit to incapabilities of this kind, or out of knowledge that it may anyway not be provided.

Whichever comes closer to the truth – or if they all have some truth in them – a theory coined by James Holstein (1992; full reference below) may here be employed. Holstein applies a micro perspectiv to social interaction in public sector organisations and finds that whenever an instituion, authority or welfare organisation sets up formal criteria, such as diagnoses, it tends to “squeeze” its clients/patients into that scheme. It “produces” the clients/patients it is set up to deal with. Out of a person with certain conditions, it produces a patient with a specific diagnose – or a care receiver with a number of needs, neatly lined up in a list, corresponding with interventions lined up equally neatly.

In Swedish elderly care, the possible conditions for which an elderly person may receive home care are listed in a code guide consisting of almost 200 pages, an international functionality standard called ICF. Every possible vulnerability, urgent human need, every requirement has to be linked to one or several of the codes in the ICF. The assistance officer, investigating the conditions for home service admittance, performs an assessment interview and is required by the National Bureau of Social and Medical Services to tic all the boxes corresponding to the catalogue of codes in the ICF. Following Holstein, we may observe how the care receiver is reformed into fitting the form – the “care-taker” is thus produced. If reocurring help requirements such as getting out of bed, getting dressed or putting food on the table are expected to turn up during the interview, they’re much more likely to be asked for by the care receiver – compared to if they are not mentioned and barely possible to even pronounce. In short, while Moldova may be “producing” care-takers that are in apparent need of having a longer talk every time the care giver shows up, Sweden may be producing care receivers who require frequent visits in order to just survive each day.

The empirical study is, however, not coming to an end quite yet, and new findings may put Holstein down the list of theory providers. Please return for updates, and please do leave comments below.

Holstein, J.A. 1992. “Producing People: Descriptive Practice in Human Service Work.” Current Research on Occupations and Professions 6:23-39.