Halfways through the third week I’m happy to find that I’ve got a reasonable grip on the assessment process in Moldova’s elderly care. Findings emanate from formal documents, interviews with social assistants, care workers and their managers, as well as a sociology scholar, and, most importantly, several care-takers.

A brief summary:

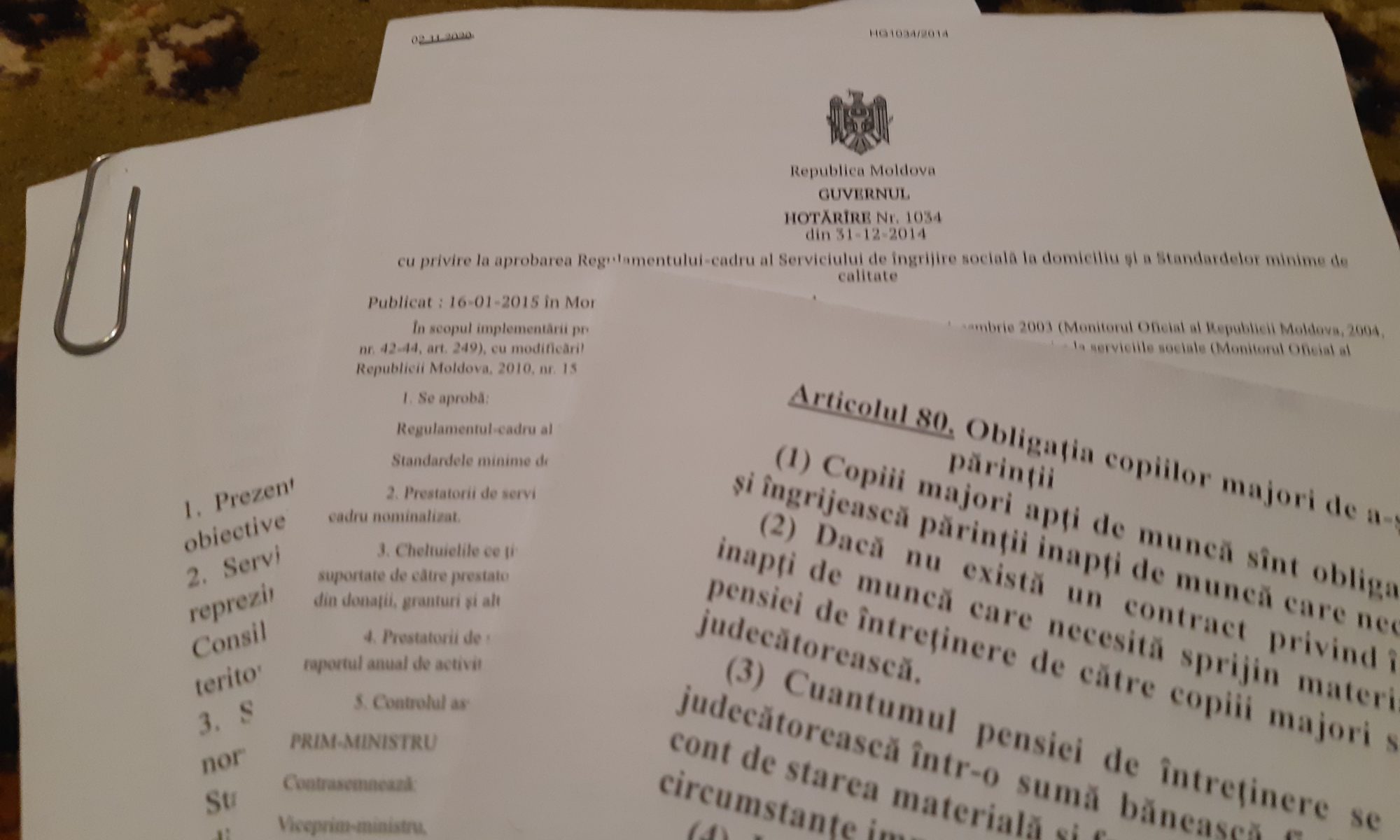

When a person of age – a pensioner, basically – experiences difficulties in everyday life, they can turn to the local social care and ask for help. Initially, an assistance officer will evaluate their needs and gather the documentation required. This includes personal documents as well as medical certificates proving disabilities and, which makes Moldova very different from Sweden, a set of papers showing that the applicant lacks any form of close relative, who would otherwise be required by law to help their kid. That’s the portal paragraph in one of the documents photographed here.

When all due documents are in place, the assistance officer formulates a decision about providing help, and a schedule for its provision. The schedule, called a grafic, basically states at what days help will be provided, and what it will consist of. Formalities include registering data about the beneficiary in several different administrative systems, that appear to mean a lot of unnecessary job for the social secretary. The formal requirements – including a form with specific questions about living standard, disabilities, needs, and other personal data about the applicant – are stated in national law, which makes Moldova a different case from Sweden, where such a form (albeit a much more detailed one) is recommended, though not juridically enforced, by the National Social Board.

As soon as formalities are in place, a social worker will be assigned to start providing the help. After three months, an evaluation of the services is required by law, but in practice, this may take a lot longer, since the beneficiary is anyway free to make a phone call to the assistance officer at any moment, should the services not match expectations. Re-evaluations – including a visit to the beneficiary’s home – will then take place roughly once per year.

If the administrative process is not carried out according to the detailed regulation, the assistance officer will be held responsible. One of my informers has had their salary reduced twice because of formal mistakes. Considering the overwhelming amount of formal requirements involved in the assessment process, one may wonder if there is anyone who can actually perform this job to perfection.

From the beneficiaries’ point of view, the system seems to provide a set of security measures, aimed at preventing ignorance, poor quality care, or mistreatment. Apart from directing themselves to the care staff – which typically is one care giver specifically for one beneficiary – or to the assistance officer, a receiver of elderly care in Moldova may also address the local administration manager, or turn directly to the National Inspection of Social Care. Considering that a substantial part of the collective of beneficiaries may suffer from dementia – a majority, according to some informants – there seems to be quite a requirement for frequent check-ups. At the same time, informers are stating that the experts from the National Inspection tend to ask beneficiaries about data that they may have a hard time remembering, like on what day a certain service was provided. “They usually don’t even know what day it is”, said one care worker.

Malmö University's MFS students' blogs!