Gabriele Zorzi, Associazione La Fara

The first part of this contribution may sound pedantic to those who already are familiar with the Lombard theme, but, I think, due to the subject’s peculiarity, it is not as well known as others. In Italy, attention has only started being paid to Lombard history in the last few decades and, to this day, the Lombard period still suffers from the Roman-centered approach to Italian historiography. In fact, talking about Lombard history in Italy still means discussing “barbarian invasions” and not the “migration period”. We all know the weight words can have in these cases. Despite this, from the second half of the twentieth century, Lombard studies, in particular the ones focusing on rich grave goods, have had their moments of fame and interest.

In this context, the peculiar provenance of our association, La Fara, was surely something we have benefitted from. Our association in fact, although it has members from several Italian regions, is based in Cividale del Friuli, the capital of the first Lombard dukedom. It was home to one of the oldest and most traditional reigns of Lombardy, and, most importantly, residence of the oldest and richest national archaeological museum on the subject which gave us access to first class sources from the beginning .

Before I start talking about archaeological finds and their relevance to the practice of reconstruction, allow me to take a step back and give some context to these “long-bearded people”. The year of the Lombard arrival in Italy is traditionally recognized as 568 C.E., as described by Paul the Deacon – the same Lombard historian who, in the eighth century, wrote the story of his people and placed their original native land in the (then almost mythical) Skåne. The migration was a relatively late one if compared to the Visigoths in Spain at the beginning of the fifth century and the Franks in Gaul, again in the fifth century. It is closer to what we know about the Bavarians, a population having a tight relationship with Lombards themselves.

Generally identifiable with a Germanic population with an eastern language (although scholars do not always agree on this point), the Lombards were known to the Roman world since the second century, becoming more and more involved in the affairs of the Eastern Roman Empire as time passed. The gradual tightening of their relations with Byzantium meant that the Lombard exercitus (i.e. troops) became part of the Byzantine army during the Greek-Gothic war that took place on Italian soil.

Lombardian relationships with Constantinople must not have been entirely consistent, and even today, analyses of the historiographical sources debate the real motivation of the Lombard descent into Italy and its legitimacy.

What is known is that the Lombard reign in Italy was never seen as legitimate either by the Pope or Byzantium. In 568, the Lombards descended into an Italy that was weakened by 30 years of Greek-Gothic war and the plague. They settled in the area without encountering a significant opposition and without the need of an armed confrontation with the local population.

Conquering the peninsula, although never completed, would keep Lombard kings and dukes busy for the next few decades. However, it seems like the creation of the first Reign in northern Italy did not require a largemilitary effort. The population which arrived in Italy from its last settlement in Pannonia (modern Hungary) brought its own mix of pagan tradition and an in fieri Christianization process, still very far from being completed and described in terms of Arian heresy.

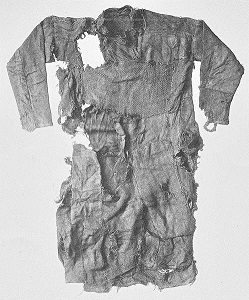

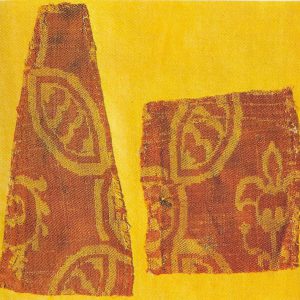

Pre-Christian clothing, especially regarding burials, are now our main source of information regarding the material culture of this population. The grave goods, dated to the end of sixth and the beginning of the seventh century, provide us with plenty of information regarding metal working, textile culture, bone and wood working, eating habits and, along with the most recent DNA studies, a glimpse of what seemed to have been a cultural rupture with the preceding situation of Gothic Italy.

The context I briefly mentioned pushed what remained of the heart of the Roman Empire into a new kind of balance, most like what was already happening in the rest of Europe. In Italian history schoolbooks, this two century period, ending with the Franks beating the Lombards in 774 AD, has become a footnote in history, dismissed in a few lines of text. Despite the fact that it was a founding element for the subsequent political situation in the Peninsula and the foundation of the art commissions known as “Rinascenza Liutprandea” by which Carolingian art would be strongly influenced.

So we are looking at two centuries of deep and sometimes traumatic changes that involved everybody, both the locals and the newcomers.

Although, centuries after , some noble families would still define themselves as “Lombards” or “following the Lombard law”, it is important to note that already at the end of their reign, the Lombards that settled in Italy must have been much different from their close ancestors. An example is the abandoning of Germanic languages for Latin, both in official papers (for example the Rothari Edict (Edictum Rothari) in the seventh century) and possibly in the spoken language since modern Italian only preserves a few Lombard words in its otherwise strictly Neo-Latin structure.

As re-creators we are mostly interested in the first immigrate generation and their first descendants. This focus is due to the Lombard’s still highly relevant tradition of burying their dead with rich grave goods, with the radical change in building techniques and the appearance of housing structures of a more “barbarian” tradition, such as partially interred houses known in field literature as grubenhauser. So, we are facing elements that break preexisting traditions and new techniques that are not going to disappear and will contribute in the formation of a new, fast changing landscape (img. 1).

But what are we talking about when we mention Lombard grave goods?

We are talking of elements that can widely vary from grave to grave, as the ethnic make-up of the Gens Langobardorum seems to have done, due to its constant contact with continental Europe’s populations. To make things more manageable, we can simplify and divide grave goods based on gender and social status. Male graves are frequently dominated by the military element: we find swords – usually pattern welded (img. 2), scramasax, spears, shields (some of them heavily decorated), axes, arrows, bow components and, most of all, belt fittings.

Based on wealth, the number and quality of these elements varies significantly. It also does this based on the time frame. Graves from the late sixth and seventh centuries show differences in decoration style and features. Along with the aforementioned elements, we can also find everyday objects such as fire steels, flint, tweezers, horse-riding related elements, game pieces and glass (img 3).

In female graves, we find a large number of belt hangings such as amulets, scissors, some sea shells, amber and glass bead necklaces, and of course radiated head fibulae (img. 4), as well as the famous “S” brooches (img. 5). Bone combs and small knives are common regardless of gender and social status.

This is, of course, a rough simplification – a glimpse that can help us contextualize the main archaeological sources that we can refer to in the re-creation field. However, there are, of course, cases that do not fit the description. One of the best examples of this is the so-called “Goldsmith’s grave” in Grupignano, which has no military element but just a silver belt buckle and three small anvils (img. 6). These exceptions give us the chance to ponder about living history and storytelling in relation with these peculiar figures that, for now, do not seem to belong in this context.

Alongside the single pieces, especially at the end of twentieth century and in the beginning of twenty-first, organic elements that escaped corruption are gaining relevance and becoming irreplaceable reference points. Here, I am talking about wood fragments of sheaths, handles and shields that provide interesting data about what kind of wood was used for each task. For example, when professor Rottoli studied tomb 40 from the “Ferrovia” burial site in Cividale del Friuli (a grave dated to the first quarter of the seventh century that La Fara is currently reconstructing), he identified the woods as willow for the shield, ash for the spear, and alder for the sheath.

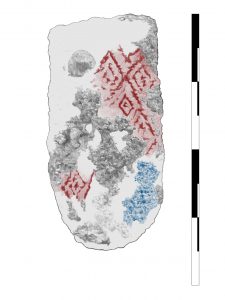

Similarly, the textile elements preserved by mineralization in contact with metal components of the belt give us valuable information in terms of fiber (wool or linen) and weave-pattern. In grave 40, for example, we have diamond twill, which you can read about in Irene Barbina’s blopost.

Having now roughly contextualized the Lombard theme, we can discuss the re-enacting and re-creation aspect.

In Italy, the Lombard and early medieval scene is relatively young. In 2010 when our group was officially founded, there was only one other Lombard group who mostly focused on historical fencing rather than grave recreation. Over the next three years the situation did not change much, but a couple of other groups focusing on fighting had formed. From 2013 to the present day, we have witnessed an explosion and, to my knowledge, there are now more than 15 “Lombard” groups.

Such a quick increase, along with the mistakes every young group is bound to make, creates two dangerous tendencies: 1) mixing recreation and ideology and 2) perhaps more worryingly, the unquestioning involvement of supposed re-creation groups in contexts related to museums or the academy.

I will try to explain myself a little better.

The first of these tendencies does not need much explanation, I think, since I suppose it is a common problem in every re-enacted era and at every latitude. If we want to describe its aspects we can still say that some of the younger groups use cultural identity, antidemocratic and macho ambition to inspire cohesion among the members.

The legitimacy of those theories is not the subject of this discussion, but you can easily imagine how the presence of these ideologized contexts has a negative influence on the quality of the re-creation work and the authenticity of information that reaches the public, as materials and sources are cherry-picked and manipulated in order to support ethnical and spiritual belonging feelings of the groups. Members of the public involved in these groups’ events are usually at risk of being taught historical and archaeological facts that are bent to support, not actual data, but the political wave of the day.

The second of the aforementioned tendencies is, possibly, the most dangerous for the whole scenario and implicitly allows the first to prosper. If in the first 10 years of the twenty-first century entering a museum was almost a utopia for a re-enacting group, the scenario has witnessed in the past few years an inversion powered by trends and the necessity of some institutions to gain visibility in the field.

The beginning of this change in an early medieval context began with a few virtuous cases in which La Fara played a role. Our event, “Anno Domini 568” (img. 7), is organized with the direct involvement of the Cividale National Museum and has been hosted on the museum’s premises for the past 5 events, placing archaologists and recreators side by side with the purpose of bringing Lombard history and archaology to a wider public.

In this very context we met Marco Valenti (img. 8): an archaeology professor, expert in open-air museums and a re-creator himself who might be the most active and motivated builder of connections between the re-creation world and academia. Valenti is in fact the mind behind the only early medieval open-air museum in Italy: the Archaeodrome in Poggibonsi (img. 9).

The Archaeodrome is a Carolingian village built just a few steps away from the original site, on which a Lombard village used to exist, by the same archaeologists who dug the site. This makes it an excellent example of how re-creation and communication can be done based on solid academic data.

In the past few years professor Valenti invested in connecting universities and re-creators, for example organizing seminars and editing books about the subject, also with the contribution of La Fara members. At the same time others moved in a similar direction, like Valentino Nizzo, manager of the Etruscan Museum in Villa Giulia. Over the past few years, he has tried to create this kind of opportunity and, as museology professor at Udine University, has allowed us to teach alongside Dr Borzacconi, manager of the Cividale National Museum, using our event as an example of museum communication.

Up to this point, the trend seemed positive, strengthened by other similar experiences involving re-enactors of different ages but, as usually happens in Italy, the trend has become popular and in a very short time it became important to involve re-enactors in museum activities in order to increase visibility on media platforms without really evaluating their preparation and suitability for this prestigious context.

I suppose it is clear how responsibilities lie on both sides in this situation. On one side, re-enactors, who are longing to prove themselves worthy of the context, re-invented themselves as re-creators by changing their group’s description (but not their approach to the subject) and proposing their group as a resource for museums and institutions. On the other side, some of these institutions, following the ones that did it first but with greater care and after rigorous evaluations, uncritically opened their doors to groups who had nothing to do with re-creation.

Recently, La Fara was requested to be a part of the opening of a very prestigious international exposition but, while we were invited by one of the scientific managers, a local group that did not even re-create the same era found its way in, by proposing they be “extras” and management approved their participation in the event. The result was an embarrassing jumble of precise recreations, materials from a different age, and fantasy elements.

I am not using this as an example for personal purposes but to show how the consequences of this kind of behavior can be deeply negative. The public, unfamiliar with the context, is often unable to tell the difference between the groups and is consequently “educated by sight” and getting the wrong information. Secondly, these “extras” are usually incompetent about history and end up either giving the wrong information or playing the part of the silent mannequin, often making it more difficult for the competent ones to be considered as reliable by the public.

Moving towards the conclusion of this glimpse into the early medieval re-construction context in Italy, I will say that historiography and archaeological sources for this era are rich, stimulating and only partially explored by re-creators. The scene is lively and rapidly evolving, and often gives us the chance to participate in international discussion and exchange. The early middle ages and its Germanic graves are becoming the common thread linking nations and individuals, in how to better approach re-creations and better communicate with the public. However, the combination of potential and the relatively young age of the scene puts it at risk of being manipulated and degraded even in an official context.

I do not believe it is possible to stop these negative tendencies from happening and, on the contrary, I think their chances to manifest are increasing. What I want to believe, though, is that there will be a chance to educate the public, giving the right tools to chose which events are worthy of taking part in and further chances for re-creators and institutions to cooperate as we did in Malmö during the conference and event: Medievalism, Public History, and Academia: the Re-creation of Early Medieval Europe, c. 400-1000.