Dr Simon Trafford, Institute of Historical Research, University of London.

Twitter: @SimonJPTrafford

On 8 September 2017, a short article with the title ‘A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics’ was published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, authored by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson and a number of other scholars. It brought DNA analysis to bear upon a skeleton dating from the C10th and found in 1877 at the famous site at Birka, in east-central Sweden not far outside Stockholm. Richly furnished with goods including eastern-style apparel, weapons, gaming pieces and two horses, the grave was interpreted on its discovery as that of a high-status male, but subsequent osteological examination in the 1970s and in 2016 had strongly suggested that the skeletal material was female; the new analysis conducted by Hedenstierna-Jonson and her colleagues confirmed on genetic grounds that the human tissue recovered from the grave was indeed biologically female.

Noting accounts of shield-maidens and female warriors in saga and early Scandinavian literature, the article asserted that the new scientific results showed that ‘the high-status grave Bj 581 on Birka was the burial of a high ranking female Viking warrior’ and that it suggested ‘that women, indeed, were able to be full members of male dominated spheres’ (Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. 2017, 858). A press release published at the same time as the article was picked up by various news outlets, and the story soon started to appear in traditional print media. But far more dramatically, though, it also exploded virally across the internet, with a rash of articles appearing in many outlets not normally much concerned with archaeology.

Popular engagement with the ‘Viking warrior women’ story is a topic of interest in its own right that reveals a lot about the relationship of scholarship and the online public realm in the age of social media and viral culture. In a fascinating series of blog posts commencing very soon after the story broke, Prof Howard Williams, an archaeologist at the University of Chester, started to catalogue reactions, exploring both the popular appeal of the Viking warrior women story and the ways in which it found expression. A number of reasons for the enormous interest in the story were clear: firstly, it was about Vikings, perennial favourites who – unusually for medieval historical figures – have a clearly defined image in popular culture, an image, which, furthermore, embraces both men and women. Secondly, the popularity of the story rested in part on a well-established and popular media trope in which new scientific evidence is seen to provide a clear and comprehensible answer to a question that has long been debated by humanities scholars but has proved intractable or insoluble. In this case the new scientific evidence in question was DNA testing, already firmly established as a firm media favourite and cure-all, apparently able to provide accurate and near-miraculous answers across a range of fields, from identification of perpetrators of crime to establishing familial connections to clarifying large-scale historical questions of population dynamics and migration. Thirdly, the idea of warrior women performs the distinctive feat of appealing simultaneously to heterosexual male fantasies of liberated Amazons and to feminist aspirations of finding powerful women in past societies.

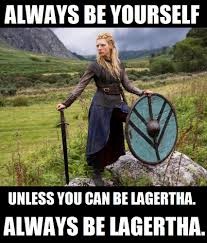

Also very notable in the online coverage were consistent themes in the way in which the story was presented. In practically every case, an allusion was made to received impressions of the Vikings and/or of warrior women from televisual culture, which generally also allowed the use of an eye-catching picture. Most frequently depicted was Lagertha, one of the central characters from the History Channel drama Vikings, but others – such as Xena, Warrior Princess or Daenerys Targaryen (from Game of Thrones) were also cited, regardless of the fact that neither of them are in any way presented as Vikings.

Reaction from scholars to the story and to the popular interest in it was mixed but before very long, some powerful criticisms had been brought to bear, notably from Prof Judith Jesch of the University of Nottingham here and here and, a little later, as we have seen, from Howard Williams. While recognising the interest of the research and welcoming the considerable attention and enthusiasm that it had attracted, a number of problems were noted. The arguments are numerous and sometimes quite complex, but summarising ruthlessly, these points were central:

(1) That the authors of the article had been too dismissive of previous scholarship and in particular had not given proper weight to the specific cultural context in which descriptions of ‘warrior women’ had occurred.

(2) That questions existed over whether the grave was actually a complete intact sealed context and whether material had been removed from it or inserted into it before excavation or mis-labelled or lost after excavation.

(3) That insufficient credit had been given for existing studies of gender fluidity in the early medieval world, including gendered grave-goods apparently ‘mis-matched’ to the occupant.

(4) That the automatic equation of interred weapons with a ‘warrior identity’ for the buried person ignored 30 years of mortuary archaeology which had comprehensively rejected the static signalling of societal roles by burial ritual.

In sum the academic critics asserted that the Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. article had been far too bold and reductive in stating definitively that Bj581 was the burial of a high-ranking warrior woman without recognising the uncertainty involved or the possibility of many other interpretations of what had been found. As Howard Williams said: ‘We might suggest that rather than a ‘female warrior’ we see a distinctive, complex social and political identity, perhaps relating to multiple individuals living and dead as well as mythological ideas, materialised in this rich burial’.

Discussion continues on the subject: in particular there was further debate at the Weaving War conference in Oslo this past December in which both Hedenstierna-Jonson and Jesch participated. Here, though, I want to think more about what the episode says about links between medieval scholarship and popular culture, and, in particular, how contemporary debates about gender powered the spectacular virality of the story. I want, in particular, to examine what is really a very simple proposition – that the huge popularity of the Vikings, in combination with the extreme hypermasculinity of the traditional Viking image has fed a hunger for female roles and involvement ever since their first emergence as a part of popular culture, but that this has been given particular impetus in recent times by a number of special circumstances.

Viking Hypermasculinity

Firstly then, to Viking men. The case for the hyper-masculinity of popular Vikings is one that requires no special pleading at all, for it is abundantly clear and constantly re-iterated in books, films, television, advertisements, cartoons, and a panoply of other media. A standard set of behaviours is attributed to Vikings across the broad range of popular culture:

- Violence, especially focused in raids,

- Restless energy and a taste for adventure,

- Barbarousness and indeed outright coarseness,

- hearty appetites for food, drink and women.

These correspond very closely with stereotypically masculine behaviours in western culture. But what differentiates the Vikings of popular culture is that they carry them to absurd extremes: they are the most violent, the most barbarous, the most hearty – and thus – according to some codings of masculinity – the most emphatically, if not rebarbatively, manly. This, it seems fair to say, is a key part of their appeal. They offer a way of enjoying behaviours and attitudes that may sometimes seem tempting – who hasn’t at times found the thought of bloody slaughter with a large axe a pleasingly direct approach to conflict resolution? – but that are completely incompatible with any form of decent modern society in which anyone would actually want to live. But because the Vikings are safely all dead and live in a distant past, there is no need to deal with any of the negative consequences.

They also – extremely importantly– have an appearance that crystallises and advertises that manliness; easy recognition of the Vikings is crucial to their iconic function in popular culture. They are almost always portrayed as tall, strong, mightily muscled and frequently depicted wielding weapons. Often, but not always, they are bristlingly bearded. Generally they are in unnecessarily small outfits which both illustrate their masculine indifference to the cold and highlight their impressive physiques. The formula is constantly repeated across a range of cultural forms, be it in TV series like Vikings or in the hyper-masculine appearance of Amon Amarth (the world’s leading Viking Metal band) or even on the covers of Viking romance novels.

Right from the very beginning of popular cultural interest in the vikings, though, there has also been a response and a resistance to this and a desire to find a place for women in this brutish and testosterone-laden world.

The warrior woman

Of course, the idea of the Viking warrior women comes, as Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. noted, from the medieval sources themselves, with references to them in both saga material and, famously, in Saxo Grammaticus’s early C13th History of the Danes. Some female warriors, namely the Valkyries, are out-and-out supernatural beings, but others seem to be humans – although the differences between the two frequently blur and both have contributed to modern ideas of Viking warrior women. They have sisters, obviously, in classical Amazons and it is likely that descriptions of the warrior women of the north have been influenced by classical parallels. From the very start it seems likely that men have been amongst the most avid proponents and consumers of the idea: then as now, the tough barbarian liberated female is a romantic and sexual fantasy for many men.

From these origins in the medieval sources, warrior women, Valkyries and shield maidens were very easily transmitted to modern imaginings of the Viking Age: they are notably present from the start of popular culture’s engagement with the Vikings, appearing, for instance in the highly romanticised artwork of the Norwegian painter Pieter Nicolai Arbo as far back as 1869.

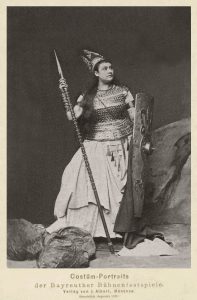

But the Valkyries were popularised above all by Wagner’s Ring Cycle in the 1870s, the costumes for which have had a massive influence on the look of the popular female Viking right down to the present.

These Valkyries are definitely supernatural, but human women who were also warriors also appear early. Helga, the heroine of the novel The Thrall of Leif the Lucky by the Swedish-American author Ottilie Liljencrantz and first published in 1902, is both beautiful and a hearty tomboy, laughing and adventuring and fighting alongside the rest.

Helga’s attractions seem indeed to have been potent, as The Thrall of Leif the Lucky became one of Hollywood’s early stabs at a Viking film, The Viking (1928), although Helga’s outfit seems to have taken a distinctly Wagnerian turn in the transition from page to screen.

Female vikings reappear in Roger Corman’s 1957 The Saga of the Viking Women and their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent but these are singularly useless Viking women, incompetent fighters and sailors and largely there to run around on screen wearing leather bikinis.

But though the shieldmaiden has been there from the beginning, there has been a considerable change in all of this over the last few years or so, as a result of two separate but intertwined developments:

1) A drive (originally within academia, but more recently popular among feminist activists outside the universities) to restore women to all periods of history and reclaim the male-dominated narrative.

2) The development of the female hero in American (and thus global) popular culture from the 1960s/1970s onwards, in such shows as Wonder Woman, The Avengers, Charlie’s Angels and The Bionic Woman. From the 1990s onwards, the female hero became even more popular in comics, TV and films such as Xena, Warrior Princess, The Fifth Element, or Jessica Jones. The most conspicuous examples at the moment are, of course, Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones and Lagertha in Vikings. Both splendidly and joyously meme-able, they provide a familiar cultural idiom by which even such rarefied oddities as Birka grave Bj581 can be articulated and interpreted to a wider audience.

Conclusions

It’s been argued very briefly here that the hypermasculine identity of the popular Viking has always fed the desire for a female equivalent. That women should colonise the most emphatically male of cultures is, of course, exceptionally pleasing, but it is the result of a perfect storm of factors that have created a large and diverse but highly appreciative audience for competent, sexy, deadly Viking warrior women. Meme culture, the eternally-popular Vikings, warrior women, feminism, the debunking narrative – they have all combined to make this sensation. But there is a particular irony that with pressing issues of gender equality currently playing out in the public square, the Vikings have become good to think with; and this is because of, rather than despite, their traditional hypermasculinity.