An exploration of eye imagery on weapons, and ornaments mainly from the 6th and 7th centuries in Northern Europe.

Part 2 of 2.

Paul Mortimer, Wulfheodenas

The Eye(s) in the Sword

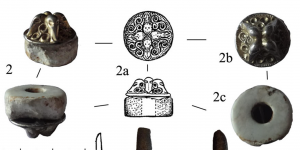

I have long suspected that some sword scabbard decoration, namely bosses/buttons[1] were meant to symbolise eyes (Mortimer 2011. 112) and I think that there is some evidence to support the suggestion. It seems that during the fifth century some warriors began to add bosses or buttons to their scabbards and there are quite a few that have been found in the weapon deposits found in the bogs in Denmark. Some similar items have been found in England too, apparently one such is a specimen decorated with Style I that used to belong to the collection of M. Braham and Lord McAlpine, (figure 43) now sold to a private buyer.

Unfortunately, the details of the Style I designs are not clear from these images which are the only ones available to us. However, another purportedly from England that once belonged to the Belgian collector and dealer Dirk Kennis, has remarkably clear details which is all the more remarkable because it is less than 2 cm in diameter. On one side is a rather grim face, whilst the opposite has a smiling one (figures 44 and 45).

The other sides each contain an eye symbol, which is very much like the eye on a sword scabbard throat belonging to a sword from Chessel Down on the Isle of Wight.[2] This eye too, has two men’s faces on either side of it (figures 46, 47 and 48).

Another find from Sandby Borg, Olund, Sweden is, I believe, significant (figure 49) as it is not the only one of this design, there are three,[3] and one of the others demonstrates how they were mounted on a sword. The boss from grave 5, Taurapilis, Lithuania, (figure 50) was found in situ on a cylinder of white chalcedony mounted on a well preserved sword.

Menghin in his 1983 book on one hundred and fifty-one significant swords almost all from northern Europe, lists the Taurapilis boss (Menghin, 1983. 205) and nine other examples with a single ‘eye’ from 5th to 7th century graves on sword from various parts of Europe.[4] In recent years in England, the PAS has recorded ten garnet and gold cloisonné examples of possible bosses from the late 6th and 7th centuries, found by detectorists. The indications are that such decorations were comparatively rare and the swords or their carriers were special in some way. The cloisonné examples especially resemble eyes, as when they are found on swords, they tend to be mounted on a pale cylinder or bulb of varying materials. The gold and garnet boss mounted on a chalcedony cylinder on the sword from grave 20 Chaouilley, France, again, does resemble an ‘eye’ with its pale coloured surround (Figure 51) (Menghin, 1983. 225).

If that is so, perhaps it is one of the eyes of Woden/Odin? Two cloisonné bosses were found within the treasures of the Staffordshire Hoard discovered by a detectorist in 2009, but only one pale stone bulb was located, of course the other stone may just have been overlooked or lost and there is no certainty they were both fixed to the same sword (figure 52).

An earlier example of a boss can be seen on the sword from Basel-Kleinhüningen, Grave 63, Switzerland (Menghin, 1983. 212). Figure 53 illustrates a reproduced example of that find (figure 53).

In this case the bulb is amber and the conical button gold. Two other pieces will suffice for illustrative purposes, one from Niederstotzingen grave 9, (figure 54) the boss is mounted on meerschaum, and the sword from Krefeld-Gellep, grave 1782 (here a reproduction), (figure 55) this time the bead is mounted on chalcedony.

A very few swords are equipped with two ‘eyes’ and I am aware of only three in the archaeological record so far. The St Dizier sword (France) is remarkable in several different ways, but what concerns us here are the bosses (figures 56 and 57).

It obviously has two, but only one is surmounted by a gold spiral; this boss is made from a pale-coloured stone. The other boss is organic and ‘blind’. The second sword with two bosses is also from northern France, and is in the Musée de Berck-sur-Mer, although what they were mounted on is unclear (figure 58).

This pair of cloisonné bosses appear at first glance to be similar, but one is larger than the other and also has a different shape in profile. The profusely decorated scabbard of the Sutton Hoo, Mound 1 sword too, has two bosses, one of which is smaller than the other (figure 59).

They were mounted on a white organic cylinder or bulb, although the exact material was never determined, in my reproduction I have used deer antler.

The craftsmen/women of the period were perfectly capable of making items that were identical if they wanted to, but in each case with the double bosses, they take care not do that. What is the message that is being given? I am sure that given my thoughts on bosses being symbolic eyes the reader will already have guessed that I am going to suggest that they are again a reference to the eyes of Woden/Odin – one being normal, the other now different and altered, or blind. If that is the case, then I would suggest that anyone who carried either a single ‘eye’ or an even rarer pair, would have been advertising that they had a special relationship with the god.

Conclusion

So what colour are a god’s eyes and does it matter? If my suggestions are accepted, and of course it is by no means certain, then quite often they are portrayed as red or red and gold and sometimes just gold – or maybe bronze…? Perhaps the colour of eyes is not so critical, but looking at the fine details of an object and attempting to prise out the stories hidden within the layers of meaning incorporated within their design certainly is.

Referring back to Neil Price’s warning from 2006, I must point out that other interpretations of the objects discussed here are, of course more than likely, but starting a discussion or taking one further forward is really important.

Endnotes

[1] These items can be known by a variety of names but for the rest of this paper we will use ‘boss’.

[2] Thanks to Stephen Pollington for recognising the link.

[3] The third is from Finnestorp, Sweden.

[4] Besides Taurapilis, Chaouilly grave 20, Krefeld-Gellep grave 1782, Niederstotzingen grave 9 and Basel-Kleinhüningen Grave 63, Menghin includes Krefeld-Gellep grave 1812 (205), Morken-Harff grave 2, Bülach grave 7, Hüttenheim grave 2 and Ziertheim.

References

Andrén, Anders; Jennber, Kristina, and Raudvere, Catharina (eds). Old Norse religion in long term perspectives. Nordic Academic Press, Stockholm 2006.

Arent, Margaret. The heroic pattern: Old Germanic helmets, Beowulf and Grettis saga, in Old Norse literature and mythology: a symposium, Polomé, Edgar C (ed) Austin 1969.

Brundle, Lisa Mary. Image and Performance, Agency and Ideology: Human Figurative Representation in Anglo-Saxon Funerary Art, AD 400 to 750. Two volumes. PhD thesis, Durham University 2014.

Bruce-Mitford, Rupert. The Sutton HooShip-Burial, volume 2, Arms, Armour and Regalia. British Museum Publications Limited. London 1978.

Christensen, Tom. Et hjelmfragment fra Gevninge, in ROMU Årsskrift fra Roskidle Museum 1999. Roskilde.

Evison, Vera. Dover Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery. Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England. 1987 London.

Gunnell, Terry. The Origins of Drama in Scandinavia. Boydell and Brewer.Woodbridge 1995.

Hårdh, Birgitta. Preliminära notiser kring detektorfynden från Uppåkra. In, Larsson och Hårdh (ed) 1998.

Helgesson, Bertil. Tributes to be Spoken of. Sacrifice and Warriors at Uppåkra. In, Larsson (ed) 2004.

Helmbrecht, Michaela. Innere Strukturen von Siedlungen und Gräberfeldern als Spiegel gesellschaftlicher Wirklichkeit? a paper presented at the 57. Internatiobalen Sachsensymposions vom 26. Bis 30. August 2006 in Münster.

Hines, John. A New Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Great Square-headed Brooches. (Reports of the Research Committee of the Society ofAntiquaries of London) Boydell and Brewer.Woodbridge 1997.

Larsson, Lars och Hårdh, Birgitta (ed). Centrala Platser o Centrala Fragorb — Samhällsstrukturen under Järnåldern. Almqvist and Wiksell International. Stockholm 1998.

Larsson, Lars. Continuity for Centuries. A Ceremonial Building and its Context at Uppåkra, Southern Sweden. Almqvist and Wiksell International 2004.

Larsson, Lars; 2007. The Iron Age ritual building at Uppåkra, southern Sweden. In Antiquity volume 81, no. 311 2007.

Menghin, Wilfried. Das Schwert im Frühen Mittelalter. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1983.

Mortimer, Paul. Woden’s Warriors; Warfare, Beliefs, Arms and Armour in Northern Europe during the 6th and 7th Centuries. Anglo-Saxon Books. Ely 2011.

Mortimer, Paul and Pollington, Stephen. Remaking the Sutton Hoo Stone; the Ansell-Roper Replica and its Context. Anglo-Saxon Books. Ely 2013.

Price, Neil. What’s in a Name? In Andrén, Jennber, and Raudvere, 2006.

Price, Neil and Mortimer, Paul. An Eye for Odin, Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo. European Journal of Archaeology 17 (3) 2014, 517–538.

Salin, Bernhard. Die Altgermanische Thierornamentik. Fourier Verlag GMBH. Wiesbaden1935 (1981).

Simek, Rudolf. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Boydell and Brewer. London 1993.

Portable Antiquities Scheme https://finds.org.uk/database

Acknowledgements:

Irene Barbina, Lisa Brundle, Matt Bunker, John Hines, Lindsay Kerr, Wayne Letting, Daniel Lindskog, Neil Price, Per Widerström, Gabriele Zorzi.