An exploration of eye imagery on weapons, and ornaments mainly from the 6th and 7th centuries in Northern Europe. Part 1 of 2.

(It’s not all about Odin![1])

Paul Mortimer, Wulfheodenas

The title of this paper comes from a conversation I had with Neil Price whilst discussing our paper, “An Eye for Odin? Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo”, we briefly discussed the idea of further investigation into the eyes of deities and thought it may be interesting to see whether their colour(s) could be discerned, which is partly the purpose of this paper.

The god with an altered eye

In An Eye for Odin, we suggest that there is good evidence that the story of Odin sacrificing an eye for wisdom may have been known at least by the late sixth century in several different regions in northern Europe. The paper assembled a number of pieces of evidence,[2] one such is that each of the eyebrows on the Sutton Hoo helmet is different to the other; the right has gold foils behind the garnets that line the lower edge of the eyebrow to reflect the light back at the viewer, while the right does not have this feature, it just has plain jewels with no backing (Bruce-Mitford, 1978, 169). We suggest that the original left brow was removed in a ritual drama enacting the elements of the story. We feel too the Roman cavalry face mask from Helvii, Gotland may have gone through a similar process (Price and Mortimer 2014. 525). The mask had been found by a detectorist but only reported by his wife to the authorities after he had died. When the find area was excavated, a possible cult site was found, as was the missing right eye from the mask which had apparently been separated and stored nearby in antiquity. Roman cavalry face masks were not usually equipped with eyes, these had been added, probably after this face-plate had been brought to Scandinavia (figure 1). There are other instances of an altered eye at Sutton Hoo, one is contained within the Stone.[3] The Stone has eight faces, four at each end and one of those at the bottom, a bearded male (labelled B1 by Bruce-Mitford, 1978. 316) has had an eye, the left, carefully chiselled away (Mortimer and Pollington 2013). (figure 2)

The helmet from Valsgärde grave 7, has a beast’s head with garnet eyes, one is bright the other dark, the same phenomena occurs on the upper beast’s head on the front of the Sutton Hoo helmet too (Bruce-Mitford, 1978. 160). With both of these examples it is the left eye that is dark. (figure 3)

An eyebrow ocular separated from the rest of the helmet has been found near Roskilde (Gevninge), Denmark (Larsson, 2007. 20 and Christensen, 1999) and another eyebrow was found close to the area where once stood the cult house at Uppåkra (Helgesson, 2004. 231). (figures 4 and 5) We think that it is likely that the eyebrows were removed from helmets during a ceremony commemorating the story of Odin’s eye. Perhaps the eyebrow was then replaced and the helmet continued to be worn? The find at Uppåkra of a ‘horned man’ with an eye struck out (Hårdh, 1998 118) seems to reinforce the importance of the story in this part of Sweden. (figure 6) The latter find is one of several such figures now known to have had an altered eye, some dating from the Viking period.

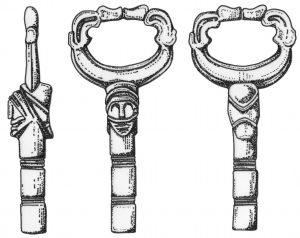

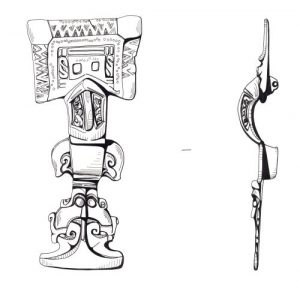

Similar figures without eyes removed are found in England, Scandinavia and the Continent. One such is the pin found in a female grave, Buckland Dover grave 161, that clearly indicate that the ‘horns’ were part of a head dress and not a helmet (Evison, 1987. 84, 251, 334 and 397). (figure 7) and two recent detector finds from Denmark also show that the horns were strapped to the head of a man.[4] (figure 8) Many of the surviving figures have had parts of their terminals broken off, but when present they usually, have been found to end in bird’s heads or a bird’s beaks. Odin, of course, in the later stories was reported to have two ravens, Huginn and Muninn, which flew around the World and reported the news back to him (Simek, 1993. 164 referring to Gylfaginning 37). Whilst some of these figures would appear to represent images of men performing a dance or ritual that must have been important over a wide area, some may have been portrayals of a deity, probably Woden, himself (Arent, 1969. 137 to 138 and Gunnell, 1995. 66 to 71).

In England and Wales, the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), effectively part of the British Museum, is an organisation where responsible detectorists can report their finds, and often representatives of the PAS are on hand at detectorist rallies to identify and record the finds. Since its establishment there have been many spectacular discoveries, particularly relating to items that are rarely, if ever, recovered from burials. Some types of horned men are a good example and so far have only been found by detectorists, as far as I am aware.[5] A portrayal, this time of a weaponised, horned man can be seen in BERK-4F2E17 from the county of Berkshire; it closely resembles the warrior/dancers depicted on helmet plates on the Sutton Hoo helmet, the helms from Valsgärde, graves 7 and 8 and one of the plates from Torslund. (figure 9) Another find from Hampshire, HAMP-B292C, would appear to be a die for making pressed plates (pressbleche) although somewhat different in form to those found on the helmets (figure 10).

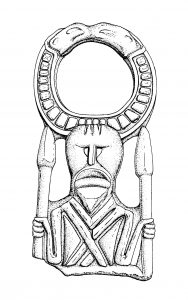

Some horned men images just consist of a male’s head with accompanying horns and birds’ head terminals, YORYM-024D31, an example from Yorkshire has garnet eyes, (figure 11) but SF-54B974 and SF-171680, both from Suffolk, depict a man’s face with the two birds’ heads configured differently, the birds’ beaks are level with the man’s ears but appear to be pointing away from them (figure 12). However, NARC-A9B3E7 (figure 13) has the beaks situated directly at the ears of the man; are we seeing Woden being told what the birds have witnessed in their journeys around the worlds? A very similar motif can be seen in this piece of fine work from Cividale, Italy. (figure 14) FAHG-8EAAA3, shows the upper body and arms as well as a head, the birds’ heads and integral pellets within the horn design, in some ways reflects similar imagery to that on the horned men (dancers) on the Sutton Hoo helmet, but unlike them, his spears are pointing upwards, how this piece was used is not known (figure 15).

A type of horned man composed of just a head but with carefully crafted horns, we have christened WAINEs (Woden Avatars In Numerous Environments) to distinguish them from other forms of horned men. Several of these are so similar in design, that it would appear the makers were using a known pattern, and as far as I know all of the known examples are detector finds. There are currently ten of these recorded and most can be found within the PAS database.[6] They tend to be made from gilded copper-alloy, some may have been a form of personal jewellery, but most have broken lugs or unusual forms of attachment on the reverse, that indicate that they were fixed to something. I am not aware of any WAINEs from anywhere other than England. Figures 16 to 21 show six examples (figures 16 to 21). These have all been made very carefully and, together with other figures, would appear to be good evidence for a fairly widespread Woden cult in England during the 6th and 7th centuries if the interpretation is correct. However, it is true that most of the horned male figures have two good eyes which have not been altered in any way but it must be remembered that Woden/Odin originally had two eyes before he gave one up to drink from the Well, and the other attributes of these miniatures, two birds, etc. would seem to indicate a reference to the god.

Very similar in design and level of craftsmanship to the WAINEs are two other relatively recent finds which may well make the link to Woden and his two ravens even more compelling. The first is from the PAS archive, SF-92CD45, but the second was sold privately sometime before the discovery of the former.[7] (figures 22 and 23) In each design, there are two birds (ravens?) that form the outline of a man’s head reflecting the general face-shape of most WAINEs. Within the overall composition are a number of holes that are the man’s eyes and mouth; the wings, tail and other ‘feathers’ represent a beard and a long moustache. Whoever made this design was creating a deliberate visual pun, based on the WAINE design and I feel, making overt references to Woden. It is obviously not a normal man dressed up, but I think an image of the god, and again they were gold-plated raising the status of the image.

Fibula

Horned men, or at least horned beings, also appear within the detail of many great square-headed brooches, and possibly other fibula. Sometimes the species identity of the face or head may be ambiguous and the horn terminals are not always of birds’ heads but of other, sometime not distinctly defined animals. The example from Baginton (left), (figure 24) clearly shows a rather manic man’s face with two beast’s heads on either side which are not birds but possibly horses, whilst the brooch from Offchurch has a smiling but perhaps, more sinister face, again between heads of an animal that is not precisely determined (Hines, 1997. Plate 20). In both cases, horns, if that is what they are, project away from the head.

The square-headed brooch from Beckford (Hines, 1997. Plate 21) (figure 25) repeats a similar design to that from Offchurch, while the specimen from Lakenheath has a moustachioed man’s face with protrusions (horns?) from the top of the head rising, following the shape of the brooch and terminating in fierce animal heads (Hines, 1997. plate 32). (figure 26) Similar devices appear from other areas than England for example from Fonnås, Norway, (figure 27) and on the brooch from Szolnok Szanda, Hungary (Hines, 1997. plate 102), (figure 28) which shows that ideas were travelling and recognised over a wide geographical area. The central creature’s heads depicted in the latter two examples, again, are rather ambiguous and could be representing an animal or a human. Exactly what each of the men/creatures is illustrating is not possible to say, but they would appear to be reflecting a number of related concepts very likely connected to the world of the supernatural, and in some ways they do have similarities to the horned men.

Returning to the Sutton Hoo helmet, there are possibly other portrayals of Woden contained within the design and the most striking is the face on the mask which is an image of transformation: a man’s face that becomes a bird (eagle?) if visualised slightly differently.[8] Together with the ‘serpent’ represented on the crest of the helm they could be a link to the story of Odin obtaining the mead of poetry; he becomes a snake in order to get to the chamber were the mead is kept and becomes an eagle to escape from Suttungr (figures 29 and 30).

When Odin reaches Asgard, he spits out the mead into a cauldron, so that other gods can become poets too (Simek, 1993. 208 refering to both Skálskaparmál and Hávamál). It is possible that at least a part of this episode is shown, again, on objects, including brooches, from the 6th and 7th centuries. Another find from the PAS, SF-DBD4E8, has a ‘tongue’ protruding from its mouth as well as two birds’ heads on either side of his head. Is the tongue symbolic of Odin/Woden speaking poetry, or of Odin spewing the mead into the bowl? (figure 31)

A similar concept is repeated on the male faces that feature on the top section of many square-headed and other brooches (fibula) even more elaborately. The suggestion came from Brundle, although she attributes it to Waugh (1995. 373) (Brundle, 2014. Volume 1, 143 and volume 2 figures 6.1 and 6.3) Most, if not all of the heads have moustaches as well as elaborate ‘tongues’ (figure 32).

Two square headed brooches from Holdenby and Kempston will serve as final examples here (Hines, 1997. Plate 79). (figure 33) There is, of course, much more going on in the designs included in most of these brooches that we do not have the space to consider in this paper.

Figurines

In his 2006 paper, Neil Price warns us not to be too ready to attribute godly status to figurines found from the Vendel and Viking periods and to be aware of other possibilities (Price, 2006. 179), so bearing his warnings in mind for the moment we will proceed by looking at some recent detector finds dated to the 5th to 6th centuries from England and see whether they have any possible divine attributes.

Possibly the most well-known currently in England is the silver example from Carlton Colville.[9] ‘The figure wears golden pants and he has a golden face too. He is quite obviously a man and well-endowed and this is emphasised with selective gilding. He is also a phallus himself (figures 34 to 36).

The figure has at least two ‘brothers’ with pretty much identical features but with varying arm postures and both of these gentlemen also had some gilding. They would seem to be connected with ideas of masculinity and fertility but while the Carlton Colville would seem to be a pendant, there is little indication of how the other two were carried, worn or attached. All of the known specimens of this type have been found in East Anglia, so a fairly limited area and it is possible that they just represent a localised cult and perhaps a deity.

There are equivalent female figurines too, several of which are holding their arms in very similar (protective?) position.[10] (figure 37 to 40) There also figurines like the one from Caistor, Lincolnshire (NLM-A243C8) that are of indeterminate gender (figure 41). They are not unlike some similar figures from Scandinavia, for instance those from Lunda, Södermanland, Sweden and elsewhere in Scandinavia.

Perhaps the most spectacular figurine found in recent years is this one from Norfolk (NMS-40A7A7) (figure 42). It resembles the horse warriors illustrated on the helmet plates on the Sutton Hoo, Valsgärde 8, Valsgärde 7, Vendel 1 and the Pliezhausen disc. It is armed with a shield and sword, but has a number of small holes which may have held other pieces of equipment, including a spear. Whether or not these portrayals are of deities, a hero or just a depiction of an ideal warrior, as some have speculated, they are impressive, detailed designs carefully executed and surely must have related to something special.[11] It must be added that the inclusion of a small figure seemingly guiding the rider’s spear on some of these helmet images, does seem to link them to the supernatural (see figure 30 as an example).

(PART II)

Endnotes

[1] …but most of it is! I have used ‘Odin’ when referring to finds from Scandinavia, but ‘Woden’ when discussing 6th and 7th century finds from England and occasionally both together.

[2] There is a list of sixteen possible examples of altered eyes and a tentative chronology in Price and Mortimer, 2014. 531. Only a few have been used in this paper. More altered eyes have been found since 2014.

[3] It has been referred to as the Sutton Hoo Whetstone, or the Sutton Hoo Sceptre.

[4] See Helmbrecht, 2006, for a useful, if dated, discussion of horned men and related imagery.

[5] It is always possible that the finds come from disturbed graves.

[6] The distribution of WAINEs is fairly widespread and they have been found in the counties of Yorkshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and Hampshire.

[7] In England, a detector find only has to be reported by law, if it contains 10% or more of silver or gold. Neither of these two items does, however, one was reported to the PAS.

[8] A similar idea is contained within the Sutton Hoo shield, where the fierce bird has a man’s face picked out in garnets and glass on its hip.

[9] He is recorded in the PAS archive as are nearly all of the figurines found in figures 35 to 44.However, at the time of writing, something has happened to the available on-line archive and some of the figurines appear to have lost their individual identifications and have been subsumed into the entry for SF-01ACA7. Some have, temporarily I hope, disappeared from the archive; this includes all the female figures and the individual entry for the Carlton Colville.

[10] Most of the figurines listed here are extensively discussed in Brundle, 2014.

[11] Arent, (1969. 139 and 142) feels that the riders are not depicting Odin – She says that, “…[t]he insignia on the helmet depicts a warrior, any warrior (hero or king) who overcomes the enemy, envisaged as primordial archenemy,…”whose act is accompanied by good omens, the birds of prey.”

References

Andrén, Anders; Jennber, Kristina, and Raudvere, Catharina (eds). Old Norse religion in long term perspectives. Nordic Academic Press, Stockholm 2006.

Arent, Margaret. The heroic pattern: Old Germanic helmets, Beowulf and Grettis saga, in Old Norse literature and mythology: a symposium, Polomé, Edgar C (ed) Austin 1969.

Brundle, Lisa Mary. Image and Performance, Agency and Ideology: Human Figurative Representation in Anglo-Saxon Funerary Art, AD 400 to 750. Two volumes. PhD thesis, Durham University 2014.

Bruce-Mitford, Rupert. The Sutton HooShip-Burial, volume 2, Arms, Armour and Regalia. British Museum Publications Limited. London 1978.

Christensen, Tom. Et hjelmfragment fra Gevninge, in ROMU Årsskrift fra Roskidle Museum 1999. Roskilde.

Evison, Vera. Dover Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery. Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England. 1987 London.

Gunnell, Terry. The Origins of Drama in Scandinavia. Boydell and Brewer.Woodbridge 1995.

Hårdh, Birgitta. Preliminära notiser kring detektorfynden från Uppåkra. In, Larsson och Hårdh (ed) 1998.

Helgesson, Bertil. Tributes to be Spoken of. Sacrifice and Warriors at Uppåkra. In, Larsson (ed) 2004.

Helmbrecht, Michaela. Innere Strukturen von Siedlungen und Gräberfeldern als Spiegel gesellschaftlicher Wirklichkeit? a paper presented at the 57. Internatiobalen Sachsensymposions vom 26. Bis 30. August 2006 in Münster.

Hines, John. A New Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Great Square-headed Brooches. (Reports of the Research Committee of the Society ofAntiquaries of London) Boydell and Brewer.Woodbridge 1997.

Larsson, Lars och Hårdh, Birgitta (ed). Centrala Platser o Centrala Fragorb — Samhällsstrukturen under Järnåldern. Almqvist and Wiksell International. Stockholm 1998.

Larsson, Lars. Continuity for Centuries. A Ceremonial Building and its Context at Uppåkra, Southern Sweden. Almqvist and Wiksell International 2004.

Larsson, Lars; 2007. The Iron Age ritual building at Uppåkra, southern Sweden. In Antiquity volume 81, no. 311 2007.

Menghin, Wilfried. Das Schwert im Frühen Mittelalter. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1983.

Mortimer, Paul. Woden’s Warriors; Warfare, Beliefs, Arms and Armour in Northern Europe during the 6th and 7th Centuries. Anglo-Saxon Books. Ely 2011.

Mortimer, Paul and Pollington, Stephen. Remaking the Sutton Hoo Stone; the Ansell-Roper Replica and its Context. Anglo-Saxon Books. Ely 2013.

Price, Neil. What’s in a Name? In Andrén, Jennber, and Raudvere, 2006.

Price, Neil and Mortimer, Paul. An Eye for Odin, Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo. European Journal of Archaeology 17 (3) 2014, 517–538.

Salin, Bernhard. Die Altgermanische Thierornamentik. Fourier Verlag GMBH. Wiesbaden1935 (1981).

Simek, Rudolf. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Boydell and Brewer. London 1993.

Portable Antiquities Scheme https://finds.org.uk/database

Acknowledgements:

Irene Barbina, Lisa Brundle, Matt Bunker, John Hines, Lindsay Kerr, Wayne Letting, Daniel Lindskog, Neil Price, Per Widerström, Gabriele Zorzi.