Of course there is no ultimate ”history of Malmö” – instead there are many histories. This is an attempt to provide some perspectives on the historical development on Malmö and the Øresund region.

The growth of medieval Malmö, a name that literally means “sand hill”, during the thirteenth century occurred for two main reasons. Firstly, due to its location just opposite the new city of Copenhagen on the other side of the Øresund, Malmö became a convenient landing place for the maritime traffic between Copenhagen and the old archbishopric in Lund. Secondly it was a part of the herring market along the Øresund which was controlled by the Hanseatic League. During early autumn, the flat sand beaches were full of fishermen bringing their catches ashore and salting the herring in barrels. Malmö’s location can be said to depend more on the conditions in and around the Øresund than on the surrounding countryside. This fact was the distinguishing feature of Malmö until the industrialization in the nineteenth century.

Historically, all of Øresund used to be part of Denmark. Northern Skåne were borderlands against the Swedish arch enemy, and the two countries were at war almost continously from 1468. During the 17th and early 18th century, Skåne became the battleground between the Swedish and Danish armies, devastating the countryside. After the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, Skåne, Halland and Blekinge (the Scanian lands) came under the possession of the Swedish Crown and Danish attempts to win Skåne back, such as the campaign that culminated in the bloody battle of Lund 1676 (almost 10 000 dead), were unsuccesful. The last military conflict between the countries were during the Napoleonic war of 1813-1814.

Lund University was founded in 1666 as a means of the ”Swedification” of Skåne. But Swedification did not happen without protest: The Danish–Swedish war drew many people out in the woods where they fought what could be seen as a guerrilla war against the Swedish invaders (though some argue that ”snapphanarna” were just thugs or robbers). The priests in Skåne were not allowed to preach in Danish any more, and a ban on importing Danish books also contributed to the strategy of turning the people in Skåne into Swedes.

During the eighteenth century, Malmö suffered a relative decline, partly attributable to its incorporation into Sweden. The Swedish conquest turned the city from a central trading town within the Danish kingdom, to a relatively marginal one in Sweden. The major function of the city, from then on, was to serve as a military stronghold.

For several reasons the the Napoleonic wars became a turning point in the history of Malmö. The city served as a major inroute for contraband to continental Europe from Britain, which led to rapid development of port facilities. Peace meant a downturn in business, but the remaining trade sanctions with Denmark were lifted, and by 1850 Malmö was the third largest harbour in Sweden and a centre of international trade. A lesson from the Napoleonic wars was also that conventional fortifications were obsolete, which meant that much of the military installations in Malmö were disbanded.

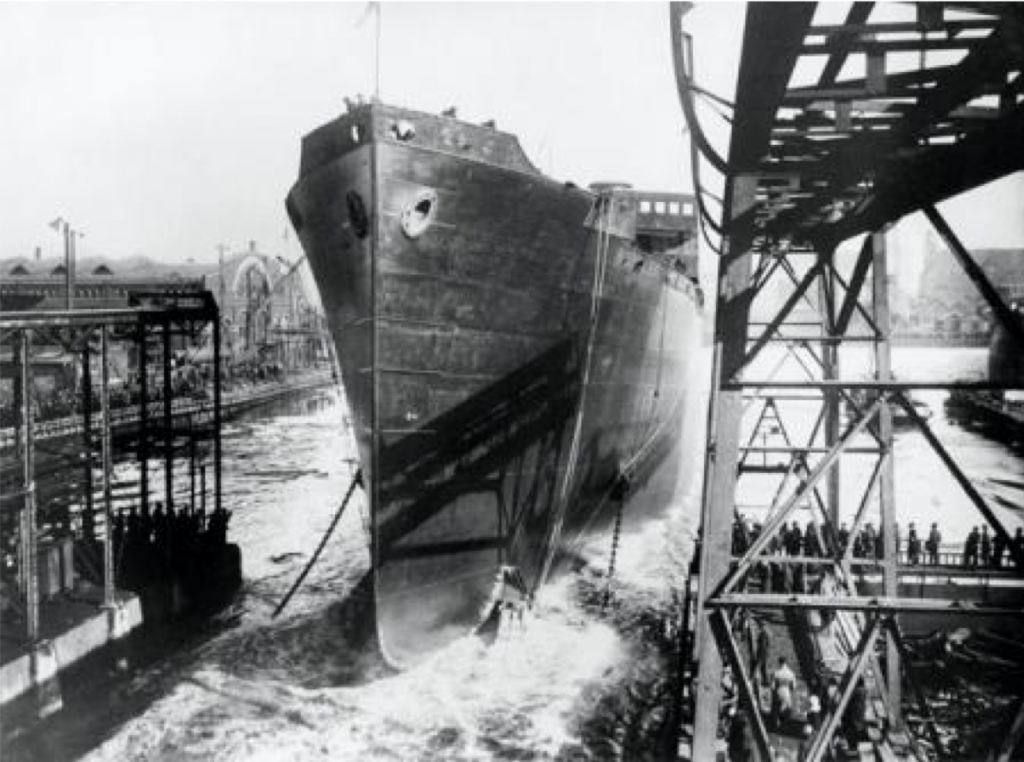

[Kockums]

Kockums Mekaniska Verkstad, founded in 1840, was vital to the development of Malmö’s early industrial economy. Initially a boiler making plant for the construction of farm machinery, located on the southern outskirts of the city, the big breakthrough came in 1859 when Kockums started supplying railway wagons for the main line (between Malmö and Lund) in southern Sweden. Over four years, Kockums produced around 400 wagons, a couple of these even being exported. In 1870 the Kockums shipyard was established and eventually all Kockum’s operations moved to the harbour area.

Malmös location, close to Denmark and continental Europe, meant that political and cultural ideas were often introduced here first – it often served as a kind of gateway to Sweden. One example of this is the labour movement. The first ever ’Swedish Workers Association’, was formed in Malmö in 1886, and prominent local Social Democrats constituted the first ’Folkets Park’ (People’s Park), and ’Folkets Hus’ (People’s House) in Malmö. Social Democrats in Malmö also formed the first Metal Workers Union in Malmö and Stockholm in the 1890s, and were subsequently to influence the direction of the trade union movement. The first newspaper with a labour movement perspective, ”Arbetet” (the Work) was founded in Malmö in 1887.

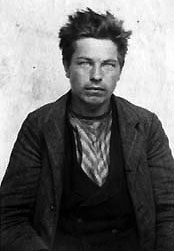

[Anton Nilsson]

The political struggle was not without conflicts. In the summer of 1908, the young activist Anton Nilson placed a home-made bomb at the ship Amalthea, which accommodated British strikebreakers in Malmö harbour. The explosion mortally wounded one man and injured about twenty others. Shortly after the attack, Nilson and his accomplices were caught by the police and were declared guilty. Nilson was sentenced to death, but was eventually released in 1917 after massive demonstrations.

[May 1st demonstration at Amiralsgatan, Malmö]

By 1914, Malmö was one of the fastest growing cities in northern Europe with almost 100 000 citizens. It was also regarded as one of the leading industrial cities of Sweden with over 10 000 employees in more than 300 factories. The early industrial economy was dominated by textile companies (like Malmö Strumpfabrik, MAB & MYA) and engineering works. This was also the year when Malmö hosted the Baltic Exhibition, which showcased art, culture and industry in a celebration of progress and modernity.

[Malmö Strumpfabrik]

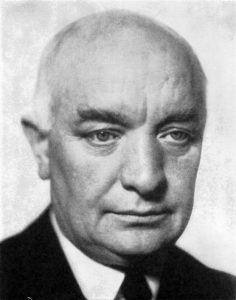

Malmö became the leading hub for the evolution of national social democracy and the labour movement – the the dominant political power in Malmö from the democratic breakthrough in the 1920s. These developments subsequently provided a blueprint for the Swedish Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson (born in a small village, Fosie, that is now part of Malmö) when he introduced his famous conception of Swedish state and society as a ’People’s Home’, in 1928 – eventually the Swedish version of the social democratic welfare state. After WWII, Malmö became the model for the social democratic vision of how the good city and the good society could look like.

The strong industry also meant that Malmö was one of the richest cities in Sweden. But during 1960s, the tide turned. First, the textile industry collapsed, and in the 1980s also the ship building. From 1965 to 1985 the number of industrial workers decreased by 40%. At first, the downturn did not lead to mass unemployment, as new jobs were created in welfare services, schools and trade, but in 1994 unemployment reached 16%.

It was clear that ”more of the same” – traditional industry – wouldn’t do the job. There was a need for new lines of thought – Malmö as a city of knowledge. To achieve this, a new university was created (the closest university have previously been in Lund, some 20 kilometers away), Malmö University, with a cross-disciplinary approach and a focus on contemporary societal challenges.

From the late nineteenth century, the interest for a fixed connection between Malmö and Copenhagen developed and involved both national governments and representatives of the two cities. In 1954, the first official delegation for collaboration between Malmö and Copenhagen, and Skåne and Sjælland, led to renewed interest in the construction of a Øresund bridge. In 1990 the Swedish and Danish governments pledged to give support to the future of regions, to ensure that the vision for Øresund was realised. The Øresund region, they argued, was a unique example of integration and cross-cultural collaboration. In 1991, the Swedish government led by the conservative PM Carl Bildt reached an agreement with the Danish government to build Øresundsbron. In July 2000 the connection between Copenhagen and Malmö opened.[1] Even though communication across Øresund had been intense in the past, with frequent ferry connections between Malmö–Copenhagen in the south as well as between Helsingborg–Helsingør in the north, Øresundsbron became a manifestation of the new regional ambitions.

Sustainable urban development framed the new political agenda. An important part of this was a new commercial/residential waterfront development: The Western Harbour, which was supposed to be a showcase of how sustainable urban development could look like. Focus here was mostly (or entirely) on environmental aspects – renewable energy etc.

[Malmö’s Western Harbour district, with the ’Turning Torso’ in the back. To the right, professor Per-Olof Hallin, department for Urban Studies, Malmö University]

Over time it has become evident that social sustainability is a major challenge for Malmö. The city is very unequal and segregated. Social tensions, violence, poverty and persistent high unemployment rates are important part of the narrative of what Malmö is today. To address this, the City of Malmö set up a commission, the commission for a socially sustainable Malmö that published their report in 2013. There is a process now to turn their suggestions into changes in policy. (read the commissions report – in English)

Today’s Malmö is a visibly multi-ethnic city: Almost half of the residents are either born abroad or has at least one foreign-born parent, and more than 150 languages are spoken in Malmö. Malmö is also a young city, the average resident is 36 years old and 40% are under the age of 30. It is also a city that strives to be innovative – actually OECD statistics indicates that Malmö is the third most innovative city in the world, based on the number of patents filed[2].

There are few texts on the history of Malmö in English – one of the more interesting is Natasha Vall’s ”Cities in Decline. A comparative history of Malmö and Newcastle after 1945”, which covers the period 1945-1995, and have the ambition to provide ”a wide perspective of post-industrialism […] and include chapters on the political, social and cultural history of both cities, as well as dealing with the major economic developments of the period.” Vall writes that

By the 1970s, these two places were seen as (what sociologist call) ’ideal types’ of late industrial decline. For most of the twentieth century, Britain and Sweden occupied polar positions in a spectrum of European economic and political systems, with Sweden characterised by sustained commitment to economic dirigisme and a strong welfare state, whilst Britain favoured state minimalism and the ’Anglo-Saxon’ economic model. This book shows how the global economic changes of the post-war period, filtered through two different political systems, were felt in the urban arena.

Some suggestions if you want to read more about Malmö – past and present:

Wikipedia (in English) – Covers most, only few factual errors.

Sabina Andrén (2009) – Urban sustainable development from a place-based and a system-based approach: Case study Malmö

Per Eliasson (2009): When the ceiling was broken. Environmental History in Malmö 1820-1920, In Björk, Fredrik et al (eds): Transcending boundaries. Environmental histories from the Øresund region. Malmö.

Ståle Holgersen (2014): The rise (and fall?) of post-industrial Malmö

Historic maps of Malmö: Are freely available here, though it can be a bit tricky to find what you are looking for in this vast archive, and many maps have been for military use and focused on fortifications etc. A few suggestions: Early map from 1652; detailed map from 1713; From 1811; In this map from 1850 urban transformation is evident; the railway and the development of the harbour can be seen in the map from 1881; Pharus plan from 1914; the large, modern city of 1947; this map shows new construction 1966-1970; and finally a map from 2002 – with the Øresund bridge and the Western harbour development.

Photos: 70 000 are freely available from the City Archives homepage; The local newspaper – Sydsvenskan – also have a quite large archive that is available online ( with watermark); interesting is also Medicinhistoriska Sällskapets photo archive with images from hospitals etc.

[1] The Øresund Bridge (more correctly the Øresund connection) is 16 kilometers long (bridge: 8 kilometers, Pepparholmen (artificial island): 4 kilometers and the Drogden tunnel: 4 kilometers).

[2] However, these statistics is based on what is defined as the ”Malmö region”, which also include Lund, 20 kilometers away (which is also part of the Øresund region).

The article provides students with a variety of historical evidences to understand the development, character,and culture of Malmo and it’s communites.Undoubtedly, Malmo is considered to be engines of economic growth and social, cultural,and political opportunities. What’s more, Malmo enjoys a strategic location and use academic knowledge to improve strongly.